May is Mental Health Awareness Month

Diagnoses save lives. Meds save lives. Therapy saves lives.

Trigger warning: This post discusses themes of suicidal ideation and alcohol abuse. Please protect your mental health and use discretion in whether or how to engage with this content.

Wednesday, October 20, 2020

I woke up with a pounding headache and sour stomach, dreading getting out of bed. I was extremely hungover, extremely confused, and extremely freaked out.

Had I tried to die by suicide last night?

I couldn’t remember, and that freaked me out. Imagine waking up, not knowing if you should be waking up.

Worse still, imagine not waking up.

The night before, I had gotten very drunk. Extremely drunk. Like at least 7 high-ABV beers drunk. And it had been a Tuesday night. And that behavior was not unusual for me. It would have been more unusual if I weren’t very drunk.

Most of the time when I drank, I was a happy and silly drunk. Sometimes an angry drunk, but not often. Sometimes - more often than I care to admit - I became a hateful drunk, but only to myself and only when I was alone. The night before was a hateful drunk night. I stayed up too late, drinking too much, and berating myself for being unlovable, ugly, fat, a burden. Telling myself that everyone around me was embarrassed to be associated with me and that they would be so much better off if I weren’t in their lives.

This isn’t new for me. For as long as I can remember, suicidal ideation has just been part of my thought process. If you haven’t experienced suicidal ideation, this is a foreign concept. The only way I can really describe it is that suicide is just …always an option for me. Since being diagnosed as neurodivergent, I’ve learned that over 60% of people who are diagnosed with autism in adulthood have reported having suicidal ideation.

I also learned early on that saying out loud that you were suicidal meant that the police would be called, you would be carted off to a mental health facility, and everyone you know would know that you were “crazy.” I learned early on that these feelings were shameful, wrong, and dangerous, so they needed to stay inside. As long as I kept these feelings to myself, I was safe.

Well, safe from everyone except myself.

That night, after berating myself, I stumbled upstairs to go to bed. I glared at myself in the mirror and saw the hateful face sneering back at me.

It was already late, I was very drunk, and I had to go to work in the morning. I knew I would have a monster hangover, so I dug the ibuprofen bottle out of the bathroom drawer. I shook three into my hand, paused, and shook almost all the contents of the bottle out into my hand. I stood (swayed) there, contemplating whether to take three painkillers or thirty.

And I woke up the next morning not knowing if I had taken three or thirty. Using context clues, I decided I had only taken three because 1. I woke up and 2. there was no evidence that I had been violently ill during the night, which is what I presumed would have happened if I had taken the entire handful.

My head was pounding. My skin felt tight. My stomach was sour. My breath still reeked of beer. There was a dull ache under my right ribs, an ache that was almost always there now and got much worse when I drank. I online-diagnosed myself with some kind of liver issue, the result of heavy and sustained drinking for most of my adult life. That pain didn’t stop me from drinking, though, even as I worried that I might someday have to get a liver transplant, and how ashamed I would be to have to tell people that.

I got ready for work and drove into the brewery. I still felt like shit and was still freaked out, but I smiled and joked with everyone like I normally did. I jokingly told a couple of coworkers how massively hungover I was until I realized that showing up to work on a Wednesday morning with a massive hangover was probably not a great sign.

Like so many times before, I swore that I would take a break from drinking, and this time, like every other time, I promised myself I would really do it. Not drinking the day after you got incredibly intoxicated is pretty easy to do - you feel like shit, you look like shit, and the results of your actions are right there and undeniable. But the day after the day after, I usually wasn’t hungover anymore, and it was easier to drink than it was to not drink. But this was the first time (that I remember) not remembering whether I had tried to die the night before, so my resolve was a little stronger this go-round.

I found an app called I Am Sober and signed up for it. I Am Sober is an app designed for people trying to get sober. It acts somewhat as a social network but also does daily check-ins to ask how your day was, if you drank, what your mood was, etc. I remember introducing myself by saying that I had woken up scared and in physical and mental pain. I read stories from people who had fallen off the wagon and beaten themselves up for it. I read stories from people who had been sober for weeks or months, and their encouragement to others that we, too, could reach those milestones.

For about four months, I stayed sober. A very small group of people (like literally maybe two) knew that I wasn’t drinking because I felt I had been drinking too much. Eventually, though, I started drinking again - not as much at first, and I switched from beer to hard seltzer - but within a few months, I was drinking at about the same level I had been.

Fast forward to the fall of 2022, and I was again experiencing massive suicidal ideation. I was crying all the time. I was back to thinking how much better off everyone in my life would be if they didn’t have to deal with me. When someone high profile dies by suicide1, I see all the beseeching social media posts that you aren’t alone and, if you think you don’t have anyone you can talk to, you can reach out to them, that one random friend from high school who you sat next to on a band trip once. Sometimes I would see someone talk about how selfish the person who died by suicide was.

In both instances, I would always think, “That’s not the case.”

For the first instance, I understand the intent behind the message and truly hope that statements like that are helpful for someone somewhere.

“Not you, though,” my brain would tell me. “They’re not talking to you.”

In the second instance, sometimes I would feel myself getting angry about being misunderstood. I would think about how I wasn’t being selfish; rather, I felt I was actually being selfless because I truly believed in my deepest core that those closest to me would have a much better life without me in it. I would be doing them a kindness by removing myself from their lives. I was coming from a place of love and mercy. Sure, some people would be sad for a while, like we’re sad when a pet dies, but eventually everyone would move past the sadness and go about their lives. I was convinced that someday they would look back and say, “She was right. It sucked for a little bit but boy are our lives improved now.”

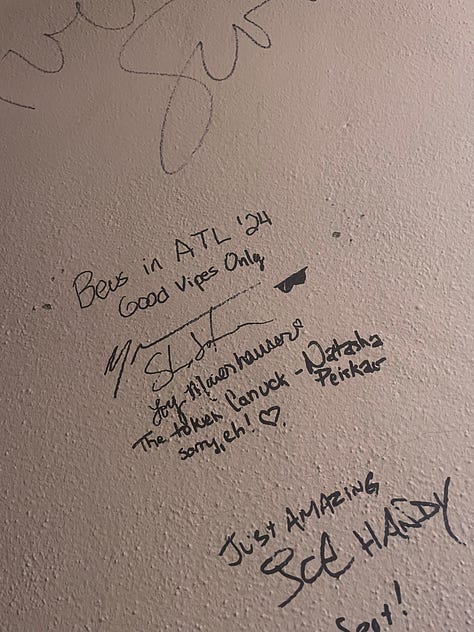

I was at one of the Great American Beer Festival judging sessions in Louisville, Colorado, in September. I was still highly suicidal, but happy that this year I would be judging with one of my closest friends. Again, it’s hard to explain the constant presence of suicidal ideation because I could be thinking how everyone would be better off without me, but also be super happy that I got to hang out with faraway friends.

We happened to be in Colorado on my birthday. My friends and I decided to go for a hike and then have lunch. During lunch, as we clinked our glasses together, one of my friends said, “We’re really happy you were born.” I smiled and then looked away quickly, thankful that I had my sunglasses on so no one could see the tears welling up in my eyes. Someone was happy that I had been born, even if I wasn’t.

Soon after I returned from that trip, I found a psychiatrist and a therapist. I decided that I did not want to keep feeling the way I was feeling and trying to self-medicate with alcohol. I had been to therapy before, with varying results, but I also knew I was never completely honest when I did go to therapy. It sounds ironic, but telling a therapist that I was suicidal seemed like a dangerous thing. Would the EMTs be knocking on my door by the time our telehealth appointment was over? Would they find a way to contact my husband and tell him?

As a late-diagnosed autistic who happens to be a woman, I learned to mask at a very young age and have been high-masking ever since. No one knew I was feeling this way, not even - especially - the people closest to me. I am extremely good at hiding my emotions and acting like everything is fine.

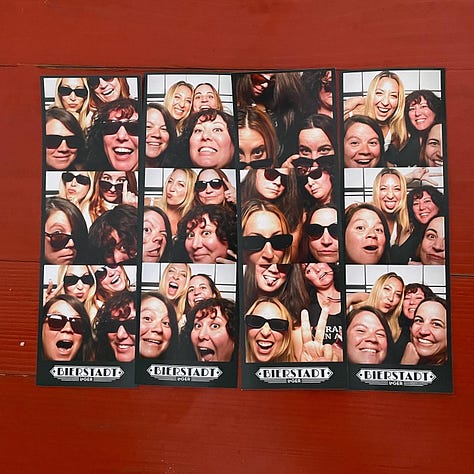

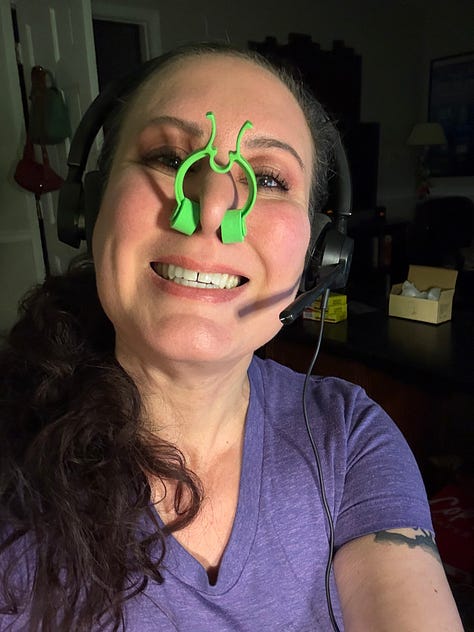

I have not had a suicidal episode since then. I don’t know if I will ever have one again. It’s been a part of me for as long as I can remember, so I’m skeptical that it is just gone without a trace. I’m happy that I’m here to tell this story and all the others. Sometimes I think about what I would have missed had I decided that night to take thirty pills instead of three. Beyond my accomplishments, I would not have been able to surprise my mom on her 70th birthday. I wouldn’t have seen my only niece graduate from high school. I wouldn’t have seen places I never thought I’d see, like Munich, London, and Prague. I wouldn’t have met some of the people I consider my closest friends.

I wouldn’t have had all of those moments, big and small. All those times someone I loved made me laugh so hard that I cried and couldn’t catch my breath, only to catch it and exhale in a loud, gleeful squeal until I dissolved into giggles again. All those times I snapped a picture of something random because it made me think of someone, and all those times someone did that for me. All of those times.

May is mental health awareness month, which is why I’m sharing this story now. The beer industry is notorious for a lot of things, being quiet about alcohol abuse and mental health being among those things. I also think a lot of neurodivergent people end up working in beer because it can be creative, not necessarily follow a traditional 9-to-5, and for other reasons.

Four people inspired me to share this story, even if none of them knew about it until I told them. Eugenia Brown is a good friend of mine and the first person I had ever seen talk openly about having suicidal ideation. Not only talk about it, but she also reassured people she was fine and didn’t need to talk about it. I understood that to my core - like I mentioned, for some people, suicidal ideation is just always there, always present. You learn to go about your life despite it being there because you learn that it will always be there, the same way the birthmark on my left shin is just always there. You can go out and laugh with friends and excel at work, and do cool things, and still have suicidal ideation.

TJ Crieghton is another friend who began openly sharing his struggles with suicidal ideation on social media in hopes that he could help other people. Before Eugenia and TJ, I had never heard anyone discuss their suicidal ideation as matter-of-factly as I thought about mine. I didn’t know other people had done things like casually think, “If I jumped off this building, where should I aim my body to make sure that I die?”

The third person is fellow beer writer David Nilsen. I wrote the first draft of this newsletter a few weeks ago and have been wavering ever since about whether I could actually hit publish and let the world know about something that had been so shameful to me for so long. Then, just a few weeks ago, Pellicle magazine released an article written by David about Brad Etheridge, a brewer who had died by suicide in 2023. In the article, David also shared his experiences with suicidal ideation. His experience was so similar to mine, and he eloquently described the same feeling about suicidal ideation that I share. I reached out to David to express my appreciation for him sharing his experience, as it lined up almost exactly with mine. Without reading his words, I may have gotten too scared to send this newsletter you are reading.

The last person who inspired me is not someone known to me personally, but all of us are familiar with the movement she began in 2009 - Tarana Burke, the creator of #MeToo.2 When I read her book, Unbound: My Story of Liberation and the Birth of the Me Too Movement, I recognized some of my own struggles in hers.

Too ashamed to tell anyone how she had been sexually abused, and then seeing people who needed to hear her story, who needed to hear that they were not alone and that it wasn’t their fault. She talked about times when she felt she had failed someone because, to truly support them, she had to share that she, too, had been sexually assaulted and was unable to. Finally, she was able to tell someone about her abuse - her child, after her child told her they had been sexually abused.

I felt this story rising in my throat as I finished Unbound. I knew it was time to share because I know everyone is struggling with issues seen and unseen, known and unknown. Realizing that sharing could potentially help someone else who is struggling, I suddenly felt compelled to write it. I had to get it out and into the world. Although I’m always a bit surprised when someone says they listen to my podcast or thanks me for my advocacy within the beer industry, I’m not going to pretend that I don’t have visibility in the industry.

I know my words have weight, and I know my words have sparked conversations and change. I know my words have comforted some and made others uncomfortable. I hope this story, these words, can help someone, too.

A couple more things before we leave each other. First, most importantly, diagnoses save lives, meds save lives, and therapy saves lives. Don’t let anyone tell you otherwise, and there is no shame in any of them. For late-diagnosed autistic adults, over 60% have reported having suicidal ideation, compared to 4.8% of neurotypical adults. Getting diagnosed as neurodivergent and going on meds for ADHD have absolutely changed my life for the better. Understanding that there is nothing inherently wrong or unlovable about me, but rather I’ve been living undiagnosed on the spectrum, struggling to get by without adequate knowledge or support for my entire life. Learning about my diagnosis helped me understand so much more about why I respond to the world the way I do, as well as communicate and advocate for my needs.

Second, I am okay. I have a wonderful support system and am fortunate enough to have access to quality health care. Also, please know that it is okay to talk to me about this. It’s an uncomfortable subject to be sure (hi, I just shared this with hundreds of people, most of whom I do not know personally), and I think that can sometimes make people think they shouldn’t address it or they need to avoid the topic.

To be clear, when I say it’s okay to talk to me about it, I do not mean it’s okay to center yourself in this narrative and expect me to help you work through your feelings about my story. It’s already scary and vulnerable to share this, and I don’t need the added burden of being expected to make you feel better about it. Please do that emotional labor yourself.

If you would like to talk to me about what I’ve written, know that I will probably cry. But also know that I cry all the time about everything, so I’m cool with crying. I’m like the Tammany Hall of criers - I cry early and often.

I’m thankful that I am still here to cry over anything and everything. I don’t want to end this with something trite like “It gets better,” because the reality is that it doesn’t get better for some people.

Still, in case no one has told you today:

There are people out there whose lives are unequivocally better because you are in them.

It seems a little weird to wrap this up with a fun sensory topic or telling you what I’m up to, so here are some pictures of things I’m grateful to have experienced since October 20, 2020.

I encourage you to use “died by suicide” rather than “committed suicide.” Saying someone committed suicide implies criminal intent and also places responsibility on the victim. The term “died by suicide” leaves space to discuss if there was a disease or disorder from which the person who lost their life suffered.

No, white actresses weren’t the first people to use #MeToo. They were just the whitest skinned women using it, so more people paid attention. This is also exactly what happened in the beer industry in 2021 - white women were not the first marginalized group in the beer industry to vocalize their harassment, but no one cared until it was white women sharing their stories.

Love you, Jenn! I am proud and so thankful to have you as a friend.

With all of my heart, thank you for being you 🧡 and I’m so glad I know you on some level. Darkness is not easy to share, but it’s in sharing that we realize how alike and connected we are as humans.